By Tom Plovie

Music Review

LET MY PEOPLE GO!

‘Traditional music’ is een brede term voor muziek die nog het best te omschrijven valt als ‘volksmuziek’. Zij wordt gekenmerkt door een orale traditie en de componisten blijken vaak onbekend. Eén van de bekendste collecties van zogenaamde ‘traditionals’ is die van de Afro-Amerikaanse slavenliederen, zoals gebundeld in ‘Slave Songs of the United States’ of in ‘Songs of the Underground Railroad’ (beiden uit de 19de eeuw). Niet alleen is er dikwijls onduidelijkheid over het ontstaan van deze liederen, maar soms ook over hun inhoud. Het was vroeger, in de Amerikaanse slavenstaten, dikwijls illegaal om slaven te leren lezen of schrijven. Afgaand op de orale traditie van overdracht, zouden er dus verborgen boodschappen in die liederen (kunnen) zitten. Denk aan cryptische instructies over waar en wanneer te ontsnappen. Eén van de bekendste ‘spirituals’ (een andere benaming) is ‘Go Down Moses’. Ik heb het nummer leren kennen in de herinterpretatie van Diamanda Galas: ‘Let My People Go’.

‘Let My People Go’ is het vaste bisnummer bij concerten van Galas. In haar versie is het een hymne voor de aidsslachtoffers. Haar broer Philip-Dimitri Galas stierf in 1986 aan de ziekte. Het was de turbulente beginperiode van de epidemie die vooral jonge homo’s stigmatiseerde en uitsloot. Zij heeft op haar vingers de zin ‘We. Are. All. HIV+’ getatoeëerd staan en wilt de stem zijn voor vele stemlozen. Al moest ze een verstoten volk uit de woestijn van onverdraagzaamheid en eenzaamheid leiden.

In ‘Go Down Moses’ wordt een vers uit het Oude Testament gebruikt: één waarin Mozes de farao, als onderdrukker van zijn volk, opdraagt om de slaven te bevrijden zodat zij met hem naar het beloofde land kunnen trekken. Uit Exodus 5, vers 1: “Dit zegt de HEER, de God van Israël: Laat mijn volk gaan, om in de woestijn ter ere van mij een feest te vieren.” In de op muziek gezette versie wordt dat:

When Israel was in Egypt’s land.

Let my people go.

Oppress’d so hard they could not stand.

Let my people go.

(Ref) Go down, Moses,

Way down in Egypt’s land.

Tell old Pharaoh:

Let my people go!

Rekening houdend met de Afro-Amerikaanse context van de 19de eeuw is de parallel tussen een farao en een toenmalige slaveneigenaar snel gelegd. Het werd geschreven als echo uit een andere tijd, maar het gaat om dezelfde roep om bevrijding. Eén van de meest indringende uitvoeringen van deze klassieker is die van Paul Robeson (1898-1976). Zijn diepe bariton en uitstekende timing om de melodie in het refrein wat te vertragen, geeft de tekst gravitas als overstemt ze een eeuwenlange traditie.

Bij de Amerikaanse Diamanda Galas (1955-) en haar herwerking van ‘Let My People Go’, zijn er 3 versies op verschillende albums te horen: een eerste keer op ‘You Must Be Certain Of The Devil’ (1988), vervolgens live op ‘Plague Mass’ (1991) en tot slot ook op ‘The Singer’ (1992). Het bewijst meteen hoe belangrijk dit nummer voor haar is. Ze herschreef de traditional met de aidsepidemie als achtergrond. Immers, met het album ‘You Must Be Certain Of The Devil’ werd haar drieluik rond aids, ‘Masque of the Red Death’ genaamd, afgerond.

Het teruggrijpen naar Bijbelverzen, om de onderdrukking en stigmatisering van aidsslachtoffers aan te klagen, was evident voor Galas. Het was vooral de katholieke kerk die homo’s veroordeelde omwille van hun ‘decadent leven’ en aids zag als de verdiende goddelijke straf. Een ander album uit de ‘Masque of the Red Death’-trilogie kreeg letterlijk die titel: ‘The Divine Punishment’. Van de oorspronkelijke Bijbelvers of liedtekst is er in haar versie nauwelijks iets terug te vinden. Met haar eigenzinnige invulling van het nummer blijft de finale boodschap toch overeind: de roep tot beëindigen van onderdrukking, een bevrijding van het virus maar vooral ook als een aanklacht voor de empathieloze medemens.

The Devil has designed my death

and he’s waiting to be sure

that plenty of his black sheep die

before he finds a cure.

O Lord Jesus, do you think I’ve served my time?

The eight legs of the Devil now are crawling up my spine.

The firm hand of the Devil now

is rocking me to sleep

I force my blind eyes open, Lord

but I’m sinking in the deep.

O Lord Jesus, do you think I’ve served my time?

The eight legs of the Devil now are crawling up my spine.

I go to sleep each evening now

dreaming of the grave

and see the friends I used to know

calling out my name.

O Lord Jesus, do you think I’ve served my time?

The eight legs of the Devil now are crawling up my spine.

O Lord Jesus, do you think I’ve served my time?

The eight legs of the Devil now are crawling up my spine.

O Lord Jesus, here’s the news from those below:

The eight legs of the Devil will not let my people go.

Haar live-versie op ‘Plague Mass’ is ongetwijfeld de meest dramatische en theatrale. Ze werd opgenomen in oktober 1990 in de kathedraal Saint John the Divine (New York). Deze seculiere mis werd door Galas halfnaakt en overgoten met ceremonieel bloed opgedragen. Met striemende stem verklankte ze het fysieke lijden dat de epidemie veroorzaakte, alsook veroordeelde ze de hypocrisie van zelfverklaarde moralisten.

Terug naar de traditional. Naast de ‘klassieke’ uitvoering van Paul Robeson en de avant-garde versie van Diamanda Galas zijn er nog veel noemenswaardige versies van deze specifieke spiritual. Een andere uitvoering om even toe te lichten, omwille van de link met klassieke muziek, is die uit het oratorium ‘The Ordering of Moses’. Zij werd geschreven door componist Robert Nathaniel Dett (1882-1943). Dit werk en zijn ‘Go Down Moses’ zijn een absoluut hoogtepunt. Dett wou de spirituals van de Afro-Amerikaanse slaven conserveren en implementeren in de populaire muziekstroming van zijn tijd, namelijk klassieke muziek. Dat doel bleek toen best controversieel. Immers, blanken beschouwden spirituals nog als ruwe en ongevormde muziek. Voor sommige zwarten was de link met een pijnlijk verleden er één om zo snel mogelijk te vergeten. Tijdens de radiopremière in 1937, werd de uitzending na ¾ van het stuk prompt afgebroken. De reden ervan blijft tot op vandaag een mysterie.

Op de melodie en tekst van ‘Go Down Moses’ schreef Dett een ronduit indrukwekkende en majestueuze fuga (een meerstemmige muziekvorm), hetgeen kan tellen als ultieme mix tussen ‘oud en nieuw’. In het vermengen van volksmuziek met de klassieke traditie stond Dett niet alleen. Zo was er bijvoorbeeld Bela Bartok (1881-1945) die in zijn eigen werk teruggreep naar Oost-Europese volksmuziek of Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857) en zijn integratie van Russische volksmelodieën. Zij schreven ermee nieuwe hoofdstukken in de klassieke muziekgeschiedenis.

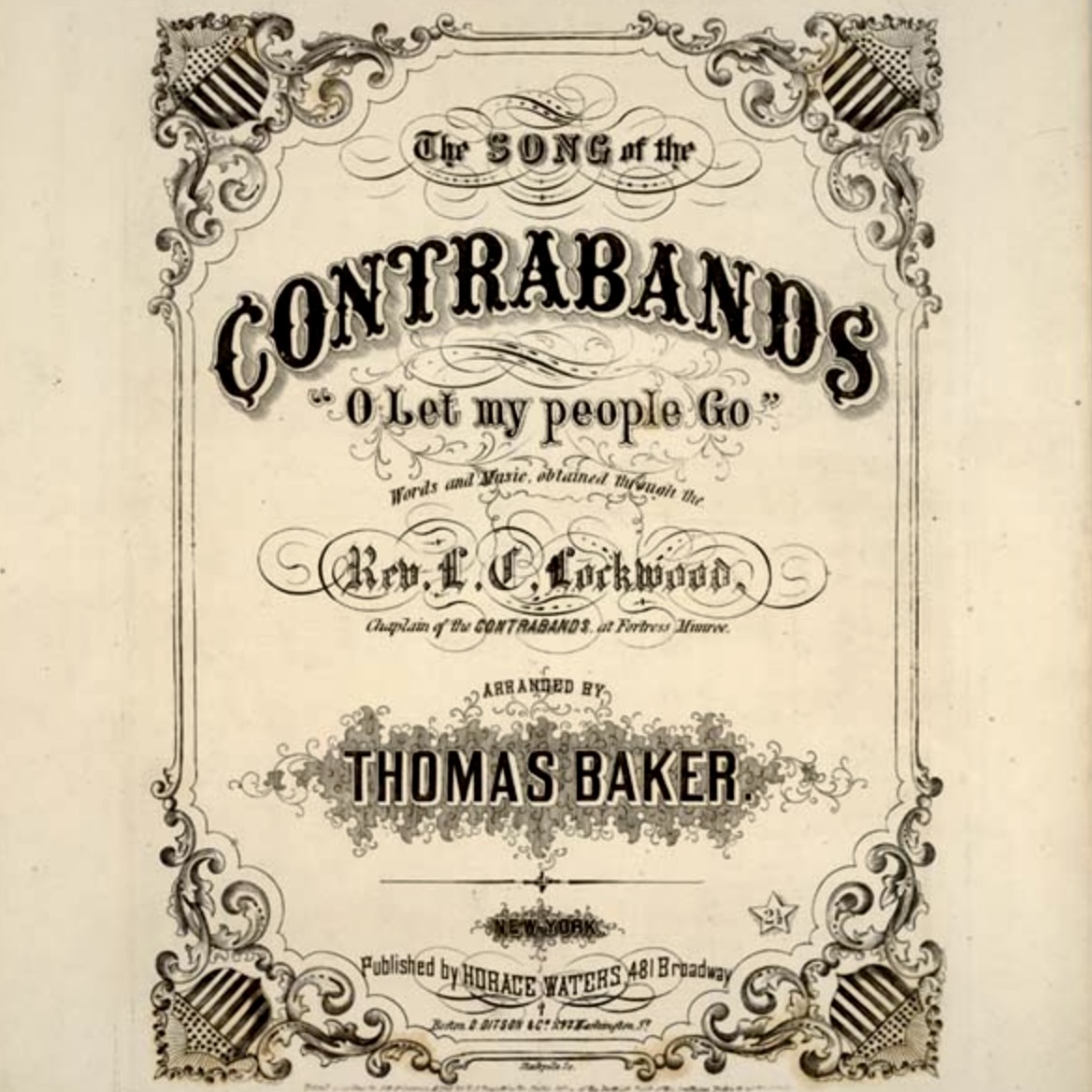

Over de oorsprong van ‘(O) Let My People Go’ / ‘Go Down Moses’ zijn de bronnen niet geheel unaniem. Toch is er consensus over het feit dat dit de eerste spiritual is, die op bladmuziek werd genoteerd en uitgegeven. Hoewel het nummer zeer populair was, werd het wonderwel niet opgenomen in de collectie van ‘Slave Songs of the United States’. Wie de eigenlijke componist(e) is, blijft voer voor veronderstellingen. Harriet Tubman (1822-1913), een Amerikaanse abolitioniste, zou het lied als code gebruikt hebben in haar strijd om slaven uit het zuiden te bevrijden via het bekende netwerk van de ‘Underground Railroad’. Door het smokkelen van minstens 300 slaven naar het noorden kreeg zij de bijnaam ‘Mozes’, hetgeen de speculatie van haar als componist alleen maar voedt.

Helaas zullen we nooit met zekerheid weten wie de componist(e) is van deze populaire en invloedrijke spiritual. Dat ze voor velen een inspiratiebron is én relevant blijft, is zeker. Een roep als ‘Let my people go!’ klinkt in deze tijden verschikkelijk actueel. Laten we, ter ere van het Oekraïense volk, dit nummer nog maar eens vanonder het stof halen en luid laten klinken.

LET MY PEOPLE GO!

/. English version

‘Traditional music’ is a broad term for music that is more clearly described as ‘folk music’. It is characterized by an oral tradition and is often written by anonymous composers. One of the best known collections of so-called ‘traditionals’ is that of the Afro-American slave songs, such as bundled in ‘Slave Songs of the United States’ or in ‘Songs of the Underground Railroad’ (both from the 19th century). Not only is there often uncertainty about the origin of these songs, but sometimes also about their content. It has often been illegal, in the American slave states, for slaves to learn to read or write. Because of the oral tradition, there would be hidden messages in these songs, often used to escape slavery. One of the most famous ‘spirituals’ (another name of the genre) is ‘Go down Moses’. I got to know the song in the reinterpretation of Diamanda Galas: ‘Let My People Go’.

‘Let My People Go’ is the popular encore on concerts by Galas. In her version it is a hymn for the AIDS victims. Her brother Philip-Dimitri Galas died of the disease in 1986. It was the turbulent beginning of the epidemic, which stigmatized and ruled out young gay men in particular. She has the sentence ‘We. Are. All. HIV+’ tattooed on her fingers and wants to be the voice for many voiceless people. As if she wants to lead an oppressed people out of a desert of intolerance and loneliness.

In ‘Go down Moses’ a verse from the Old Testament is used: one in which Moses instructs the Pharaoh, as a suppressor of his people, to free the slaves so they can move with him to the Promised Land. From Exodus 5, verse 1: “This is what the LORD, the God of Israel, says: ‘Let my people go, so that they may hold a festival to me in the wilderness.’” In the music-based version the lyrics are:

When Israel was in Egypt’s land.

Let my people go.

Oppress’d so hard they could not stand.

Let my people go.

(Ref) Go down, Moses,

Way down in Egypt’s land.

Tell old Pharaoh:

Let my people go!

Taking into account the African-American context of the 19th century, the parallel between a Pharaoh and a slave owner is quickly made. It was written as an echo from another time, but it is the same call for liberation. One of the most compelling versions of this classic is Paul Robeson’s (1898-1976). His deep baritone and excellent timing to slow down the melody in the chorus, gives the text gravitas as if she overcomes an age-old tradition.

In the new interpretation of ‘Let My People Go’ by American singer Diamanda Galas (1955-) 3 versions on different albums are known: a first recording on ‘You Must Be Certain Of The Devil’ (1988), a second one live on ‘Plague Mass’ (1991) and the song appears also on ‘The Singer’ (1992). It proves immediately how important this song is for her. She rewrote the traditional with the AIDS epidemic as a background. After all, with the album ‘You Must Be Certain Of The Devil’ she completed her triptych around AIDS, which is called ‘Masque of the Red Death’.

Using Bible verses, to condemn the oppression and stigmatization of AIDS victims, was obvious to Galas. Above all, it was the Catholic church that condemned gays for their ‘decadent life style’ and they saw AIDS as their divine punishment. Another album of the ‘Masque of the Red Death’-trilogy was literally entitled: ‘The Divine Punishment’. Of the original Bible verse or lyrics little can be found in her version. With her idiosyncratic interpretation of the song the message remains: the call to end oppression, a liberation from the virus but above all as a condemnation of the empathyless fellow human being.

The Devil has designed my death

and he’s waiting to be sure

that plenty of his black sheep die

before he finds a cure.

O LORD JESUS, do you think I’ve served my time?

The eight legs of the Devil now are crawling up my spine.

The firm hand of the Devil now

is rocking me to sleep

I force my blind eyes open, Lord

but I’m sinking in the deep.

O LORD JESUS, do you think I’ve served my time?

The eight legs of the Devil now are crawling up my spine.

I go to sleep each evening now

dreaming of the grave

and see the friends I used to know

calling out my name.

O LORD JESUS, do you think I’ve served my time?

The eight legs of the Devil now are crawling up my spine.

O LORD JESUS, do you think I’ve served my time?

The eight legs of the Devil now are crawling up my spine.

O LORD JESUS, here’s the news from those below:

The eight legs of the Devil will not let my people go.

Her live version on ‘Plague Mass’ is undoubtedly the most dramatic and theatrical one. It was recorded in October 1990 in the Cathedral Saint John the Divine (New York). This secular mass was performed by Galas half naked and drenched with ceremonial blood. With a strong voice, she embodied the physical suffering that was caused by the epidemic and condemned the hypocrisy of self-declared moralists.

Back to the ‘Traditional’. In between the ‘classic’ performance of Paul Robeson and the avant-garde version of Diamanda Galas, there exists many notable versions of this spiritual. Another version to talk about, because of the link with classical music, is the one from the oratorio ‘The Ordering of Moses’. It was written by composer Robert Nathaniel Dett (1882-1943). This work and his ‘Go down Moses’ are an absolute highlight. Dett wanted to preserve and implement the spirituals of the Afro-American slaves in the popular musical movement of his era, which was classical music. That goal proved to be quite controversial at that time. After all, white people considered spirituals as raw and unformed music. For some black people, the link with a painful past was one to forget as soon as possible. During the radio broadcast in 1937, the music was aborted after ¾ of the piece. The reason why remains a mystery to date.

To the melody and text of ‘Go down Moses’, Dett wrote a truly impressive and majestic fugue (a form of music with multiple voices), which can be considered as the ultimate mix between ‘old and new’. In blending folk music with the classical tradition, Dett was not alone. For example, there was Bela Bartok (1881-1945) who in his own work integrated Eastern European folk music or Mikhail Glinka (1804-1857) and his integration of Russian folk melodies. They truly wrote new chapters in classical music history.

On the origin of ‘(O) Let My People Go’ / ‘Go down Moses’ the sources are not entirely unanimous. Yet there is consensus that this is the first spiritual, which was noted and published on sheet music. Although the song was very popular, it was not included in the collection of ‘Slave Songs of the United States’. The answer on the question of who’s the actual composer is subject to assumptions. Harriet Tubman (1822-1913), an American abolitionist, would have used the song as a means to free slaves from the south using the well-known network of the ‘Underground Railroad’. By smuggling at least 300 slaves to the north, she was nicknamed ‘Moses’, which only feeds the speculation of her as a composer.

Unfortunately, we will never know the actual composer of this popular and influential spiritual. It is certain that this song remains a source of inspiration for many and stays relevant too. A call like ‘Let my people go!’ seems particularly pertinent these days. In honor of the Ukrainian people, let’s play this song again – “at maximum volume only” as Galas often suggests to play her music.

Tags

Music Review

Concert Review

Diamanda Galàs

Plague Mass

Paul Robeson

Masque of the Red Death

Author

Tom Plovie - Lokeren - © 15 maart 2022

Sources

Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia- Sticky Notes: The Classical Music Podcast, S8 E138 R. Nathaniel Dell: The Ordering of Moses

- Diamanda Galas: The Shit of God, p. 25: Let My People Go (lyrics)

Artist

Diamanda Galàs Paul Robeson

Video

Paul Robeson- Nathaniel Dett (0:31-2:20)

- Diamanda Galas (live version)